A bold and irreverent protest 50 years ago put a renewed women’s liberation movement on the public map—and offers important lessons for today’s resistance.

By Laura Tanenbaum and Mark Engler

(Published on August 7, 2018 in The Nation)

On September 7, 1968, more than a hundred women gathered to protest on the boardwalk

of Atlantic City, New Jersey. Organized by a recently formed group called New York

Radical Women, the demonstration targeted an annual televised event, which, the women

argued, served as a potent symbol of the country’s entrenched sexism: the Miss America

beauty pageant. With a day of street theater, they announced the arrival of a new, more

militant women’s movement—one with renewed significance in the #MeToo era.

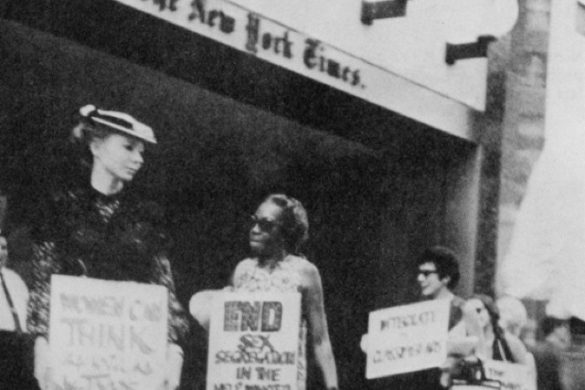

On the boardwalk, women marched with signs reading, “Can makeup cover the wounds

of our oppression?” and “If you want meat, go the butcher.” One group crowned a live

sheep the winner of the beauty contest, while another auctioned off a lanky, blonde Miss

America effigy (“Step right up! How much am I offered for this number one piece of

prime American property?! She sings in the kitchen, hums at the typewriter, purrs in

bed!”). In another act, the participants threw “symbols of oppression”—including girdles,

high heels, and hair curlers—into a bin dubbed the Freedom Trashcan. (Contrary to the

bra-burning myth invented by the media as a result of the event, no undergarments were

actually incinerated.)

Finally, a small group acquired tickets and infiltrated the hall, briefly disrupting the

pageant by unfurling a banner that read “Women’s Liberation” and chanting during one

of the televised speeches. “It was the most wonderful celebratory mood,” Peggy Dobbins,

one of the participants, said recently. “We knew we were on the right track.”

The protest became national news, catapulting the era’s new wave of feminist activism

into public consciousness. As Carol Hanisch later recounted, “When we read the morning

papers, we knew our immediate goal had been accomplished: Alongside the headline of a

new Miss America being crowned was the news that a Women’s Liberation Movement

was afoot in the land and that it was going to demand a whole lot more than ‘equal pay

for equal work.’ We were deluged with letters, more than our small group could possibly

answer, many passionately saying ‘I’ve been waiting all my life for something like this to

come along.’”

Fifty years later—when we are governed by an alleged rapist who once owned a rival

beauty pageant—the protest remains all-too relevant. It offers important lessons not only

for those who, in the wake of #MeToo, are organizing against misogyny and harassment,

but for all who seek to understand how social movements can effectively build resistance

today.

A Perfect Symbol of Oppression

A first lesson is that a well-chosen, symbolically rich target can help provoke the kind of

cultural shifts that lay the groundwork for widespread change.

At the time of the demonstration, Miss America protesters had to push back against

fellow activists and members of the public who saw their energies as misspent. “Some

male reactionaries in the Left still think Women’s Liberation ‘frivolous’ in the face of

‘larger, more important’ revolutionary problems,” writer and activist Robin Morgan

wrote shortly after the event. Moreover, some questioned why a pageant should be a

focus of dissent. After all, by expressing their disdain for the event, the protesters would

win no legal or legislative changes.

The members of New York Radical Women, however, recognized the pageant’s potency

as a cultural icon. “Everybody tuned into Miss America back them—this was like the

Oscars,” one of the protesters, Alix Kates Shulman, remembered. Hanisch, one of the

main organizers, further explained, “Here was this American icon—the Miss America

Pageant—telling women what to look like, what to wear, how to wear it, how to walk,

how to speak, what to say (and what not to say) to be considered attractive.”

Speaking on a talk show after the protest, activist Rosalyn Baxendall remarked, “Every

day in a woman’s life is a walking Miss America contest.”

Going after Miss America, moreover, allowed the radicals to draw connections between

issues. In their press release, they pointed out how the pageant propped up consumerism

(“Miss America is a walking commercial for the pageant’s sponsors. Wind her up and she

plugs your product…”) and war (“last year she went to Vietnam to pep-talk our

husbands, fathers, sons and boyfriends into dying and killing with a better spirit…). They

also decried the historical exclusion of nonwhite women from the pageant and the racism

of the beauty standards it upheld, an issue that the legendary African-American activist

and lawyer Flo Kennedy fought to get on the New York Radical Women’s agenda.

The protest helped trigger a torrent of organizing and consciousness-raising. This wave of

activity, in turn, helped produce substantial reforms—in reproductive rights, equal access

to education, and employment equality, among other areas. The era’s radicals also

established the analytical framework for the concept of sexual harassment, seeing it, like

the pageant, as less about sex than about power and the desire to keep women in their

place.

Like the pageant protest, the most profound impact of the #MeToo movement may have

less to do with its effect on any one specific target than with its ability to usher in a

cultural reckoning. #MeToo has sometimes been discussed in narrow, legalistic terms, as

seeking to hold specific men in high-level positions accountable for improper and

sometimes criminal behavior. But its more radical implications come from identifying the

power of patriarchy across a range of institutions—connecting the behaviors of notorious

harassers with the types of pervasive and persistent sexism that prevail across workplaces

and highlighting the routine abuses faced by workers ranging from hotel housekeepers to

restaurant servers to journalists to graduate students. Some of the most promising

organizing is going beyond the naming abusers and toward creating spaces where those

affected can share stories, build solidarity, and develop collective strategies for action.

For example, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, a worker-based human-rights

organization, has made political education about sexual harassment a priority among its

members, helping male workers see the importance of the issue and understand it as

linked with other workplace concerns. As a result, they are including protections against

harassment in the agreements they are brokering with restaurants chains.

It’s About More Than Numbers

A second lesson is that the design and drama of a social movement action can be more

important that sheer numbers of participants. Most activists who were present estimate

that perhaps 200 women took part in the Miss America protest, a modest number.

Yet the action was planned as a boisterous and theatrical affair designed to engage the

public—what activists at the time called a “zap.” Further feminist zaps would be

deployed when many of the same women went on to form the group WITCH, which

famously put a hex on Wall Street on Halloween of 1968. Similar guerrilla-theater tactics

were later used to great effect in the 1980s by HIV/AIDS activists who came together in

ACT UP.

Not only were these actions catchy and entertaining; they were disruptive, with

participants risking arrest and professional sanction. In the case of the Miss America

protest, Dobbins was arrested and charged with “emitting a noxious odor” after spraying

Toni Home Permanent in the aisles of the Convention Hall. The hair-product brand was a

pageant sponsor and infamous among women for its pungent smell. “The corporate

sponsorship of women’s oppression stank then,” Dobbins said recently, “and it stinks

still.”

The action was also helped by a savvy media strategy. The protest’s press release

advised, “We reject patronizing reportage. Only newswomen will be recognized.” And

the participants held to their word, with lasting result: Female journalists at the time were

often restricted to the society pages or a few other limited beats. By insisting on speaking

only to women, feminists not only garnered more sympathetic coverage, they helped

these reporters get a wider range of assignments.

The 2017 Women’s March—held the weekend of Trump’s inauguration—succeeded in

becoming the largest single-day demonstration in US history. Yet not every action will be

so well-attended, and activists should not be stuck seeking ever-larger numbers. The

willingness of small groups to take on higher-risk actions, smartly conceived, can expand

a movement’s tactical repertoire.

Certainly, the media strategies of 50 years ago, while shrewd in their time, must be

adapted for relevance in a saturated news environment that has been transformed by

Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. #MeToo, like #Occupy and #BlackLivesMatter before

it, showed that social media can effectively be used to highlight events that might

otherwise be underreported. Moreover, while mainstream media are often ill equipped to

understand social movements and tend to favor stories about powerful individuals, the

creative use of alternative media can elevate a wider range of voices and galvanize people

who begin to realize how pervasive an issue is in their communities.

The Personal Is Still Political

While the Miss America demonstration was aimed at engaging a broad public, it existed

within a movement that incorporated different approaches to effecting change, including

consciousness-raising, direct action, institutional lobbying, organizing, and the creation

of alternative institutions. And this is a last important lesson of the protest: that different

methods of movement building can complement and enhance one another.

Consciousness-raising—a term attributed to Kathie Sarachild, a member of New York

Radical Women and one of the pageant protest’s organizers—is one of the most well-

known and misunderstood tactics of the radical-feminist movement. Rooted in the idea

that the “personal is political,” it is a process through which groups of women would

describe their experiences and make connections to the wider political context. Women

joining the movement and participating in these sessions quickly recognized that troubles

they had perceived as individual problems were widely shared—and rooted in social,

political, and economic structures that were working to their disadvantage.

But consciousness-raising, which is still effectively used by organizers today, was never

meant to end with personal insight or group bonding. Rather, the originators of the

practice intended it to fuel protest and organizing campaigns that would be connected to

the lived experiences of oppression. Indeed, as Hanisch explained, “The idea for the Miss

America protest came out of group consciousness-raising in New York Radical Women.

We had discussed how we were all pressured to act and look in certain ways which we

found limiting, uncomfortable, and oppressive.” After reflecting on their experiences

watching the pageant, the feminists realized the event’s power—and this led directly to

the plan for action. “The protest was so successful because we had struck a chord in most

women’s lives by understanding our own,” Hanisch said.

Just as personal transformation can motivate public action, attention-grabbing zaps and

mass mobilizations can encourage organizing and the creation of lasting alternative

institutions. “The week before the [Miss America] demonstration there had been 30

women at the New York Radical Women meeting,” Robin Morgan reported; “the week

after, there were approximately a 150.” Hanisch argued that the national press also led to

a flowering of local organizations elsewhere, giving women “the nudge they needed to

form their own groups. They no longer felt so alone and isolated.”

Of course, the process of building a multi-pronged movement did not always go

smoothly. Feminist groups struggled to absorb the flood of new recruits. They

experienced schisms and internal strife; New York Radical Women itself split within six

months of the Miss America action. And, as feminist scholars such as Alice Echols and

Jo Freeman have detailed, small groups could grow inward-looking and “encapsulated,”

more preoccupied with their own communities than with changing dominant structures.

Yet in spite of these challenges, the organizing that followed the 1968 protest made a

serious impact, both in terms of policy and the creation of institutions—including

feminist presses and book stores, women’s-studies programs, rape-crisis centers,

women’s-health clinics, battered-women’s shelters, and cooperative daycare

centers—which altered the cultural climate for years after the movement’s period of peak

visibility.

#MeToo has once again demonstrated the power that can be unleashed when shared

personal experience becomes an insistent and undeniable demand for social change. The

task now is to connect this awareness of injustice with public mobilization and sustained

organizing. For if the Miss America protest shows nothing else, it is that few things are as

transformative as the experience of collective action. “I don’t ever remember feeling that

powerful up to that point,” participant Bev Grant said. “Because it was all women. And

there was just this sense of, ‘Oh my God, look what we can do.’”