Smart organizing during whirlwind moments seeds the ground for new waves of action in the future.

By Mark Engler

(Published in The Atlantic.)

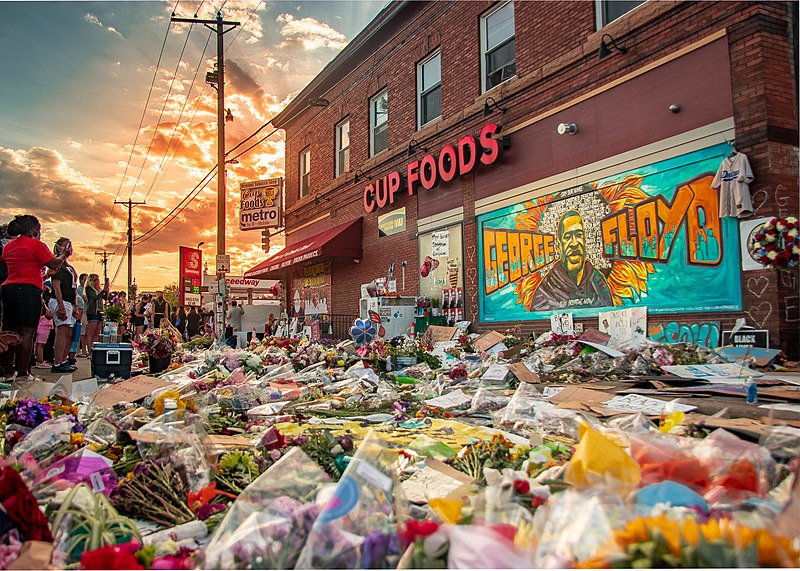

Since the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25, crowds demanding racial justice have surged into public spaces across the country and throughout the world—with solidarity actions springing up in South Korea and South Africa, Argentina and Australia. Domestically, demonstrations have materialized not only in major cities, but also in small-town America, including places with deeply conservative populations. As several political scientists noted in the Washington Post, “The United States rarely has protests in this combination of size, intensity and frequency; it usually has big protests or sustained protests, but not both.”

When will the protests end? And what will it mean when they do? Although all waves of mass protest are different, they tend to follow a similar course. Demonstrators can’t stay in the streets forever. When they relent, though, that doesn’t mean they have stopped caring—or that the movement is over. If protests die, their goals and ideas can survive as the ongoing work of organizing continues.

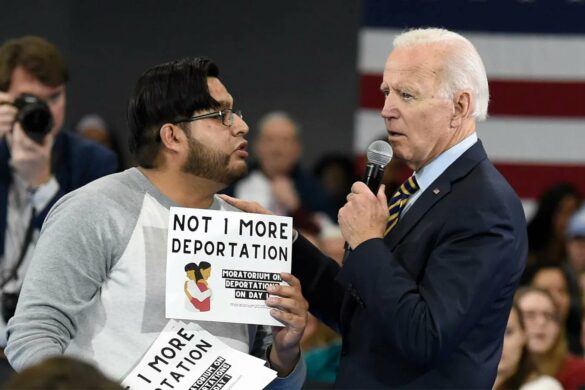

Highly visible protests are only one part of social movements. While movements as a whole are propelled by long-term vision and deep-seated grievances, mass protests in particular emerge in response to what some theorists call “trigger events.” Here, a dramatic incident such as a natural disaster, a media exposé, a political scandal, or a killing may ignite passions and prompt outrage, sending people into the streets. A moment of unrest may extend for weeks or even months, especially when guided skillfully by organizers.

But activists trying to sustain momentum face serious headwinds. The media is fickle in its attention, and a flitting spotlight makes it harder for activists to be seen and to draw in new people. Already, although issues of racial justice raised by the protest remain a critical part of public discussion, headlines have moved away from focus on street actions and instead turned to stories such as President Trump’s reelection rallies and the surge in new coronavirus cases.

Another factor that can slow protests is that they demand a serious commitment of time and energy from participants; eventually, many tire out. As the weeks stretch on, the pressures of ordinary life begin to reassert themselves, and people must return to responsibilities that they might have set aside in a moment of crisis. Some of those who are most committed may be encumbered with arrest and subsequent, time-consuming legal entanglements. As just one example, protests at the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 2000 resulted in hundreds of arrests, bail as high as $1 million for those deemed “ringleaders,” and a subsequent legal battle that took years to resolve.

Either due to strategic calculation or exhaustion, some protest participants may shift their energies into more institutional channels. For instance, many of those who protested the Iraq War in early 2003 turned to focus on electoral work by the summer or fall, believing that the campaigns of candidates such as Howard Dean represented the best hope of unseating George W. Bush and thereby repudiating the war.

Political officials and other targets may offer short-term concessions to movements or invite high-profile protesters to sit on commissions to propose policy solutions. Optimists might cite these as positive examples of reform. Critics are more likely to label them examples of “cooptation” and point out that the changes enacted are only small steps toward addressing the root causes of an issue. Depending on the particulars, either or both assessments could be right (although the fact that corporate PR agencies recommend task forces and advisory boards as means of “managing activism” would suggest that skepticism is warranted). Regardless, the perception that something is being done to address protesters’ concerns can serve to blunt public discontent.

For all of these reasons, and with the passage of time, the initial shock of the trigger event fades. At that point, mass protests decline and other components of social movements tend to come back to the fore—that is, until a new trigger reignites the prospect of revolt.

Mass mobilizations take place within a wider ecosystem of social movement activity. Other pieces of movements include building long-term organizations—such as unions and community groups—and taking on “inside-game” work, like electoral campaigns and legislative lobbying. Still other segments of a movement might devote themselves to political education, cultivating personal transformation at the individual level (through spiritual and cultural programs), or to building alternative institutions (such as community spaces, bookstores, food co-ops, and independent media). All of these types of organizing contribute to the movement’s long-term impact, even if they might have varying importance at different times in a movement’s lifecycle.

When a period of peak protest inevitably fades, media commentators often declare the movement dead and decry its inability to realize lasting change. Occupy Wall Street, for example, is regularly cited as a failure, despite the fact that it contributed to a major change in the conversation about economic inequality in America and helped pave the way for the mainstream acceptance of candidates such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders. It is more accurate to say that mass protests come and go in cycles. Organizers laboring on the changed terrain that large-scale mobilizations leave behind can help prepare for future uprisings—establishing infrastructure that can help movements respond when new trigger events launch fresh waves of indignation. The current round of racial justice actions, for instance, owes a significant part of its vitality to the Black Lives Matter protests that erupted during the Obama administration and the organizing that has continued since.

More than ever, America has awakened to patterns of structural racism and the systemic nature of police abuses. Until that system changes, we should expect that even as older waves of mass demonstration recede, new ones are sure to rise.

__________

Photo credit: Vasanth Rajkumar / Wikimedia Commons.