By Mark Engler

(Published in Waging Nonviolence, November 21, 2016; Photo credit Twitter/AllOfUs2016)

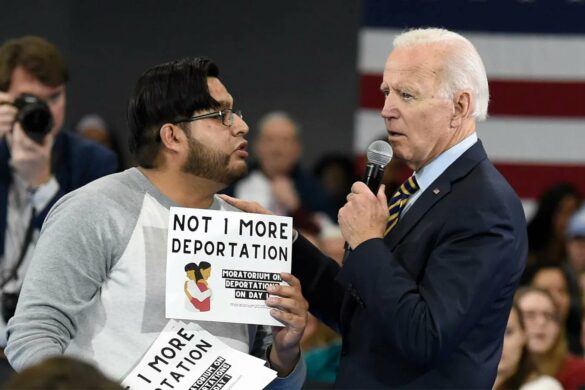

On November 14, six days after the election of Donald Trump, some 40 young people walked into the office of New York Sen. Chuck Schumer, calling on the senior lawmaker to step aside in his bid to be Senate minority leader. Carrying a banner that read “Wall St. Democrats Failed Us,” they argued that Schumer, who has received more than $3 million in campaign contributions from the securities and investment industry in the last five years, was exactly the wrong figure to lead the opposition to Donald Trump. When the senator refused to meet with them, the protesters sat on the floor to barricade the office, filling the halls of the Hart Office Building with protest songs. In the end, 17 were arrested.

Asked about the purpose of the protest, organizer Yong Jung Cho stated, “The establishment Democrats have failed the American people. The establishment Democrats failed to stop Donald Trump.” Another leader, Waleed Shahid, added that the group, #AllOfUs, would continue to target Democratic senators “who don’t do anything they can to filibuster Trump’s legislation that promotes his hatred or his greed.”

At a time when so many people are furious at Donald Trump and terrified of his agenda, some will ask why these activists are targeting leading Democrats. After all, isn’t that attacking the wrong side?

A look at the history of social movements under hostile governments provides a counterintuitive answer. At a time when Donald Trump has risen to the presidency by railing against the Washington establishment and upending the traditional rules of politics, the Democratic Party’s propensity for compromise and triangulation only plays into his hands. The only hope for unseating Trump and minimizing the damage of his agenda will be to fight his racist right-wing populism with a progressive vision. This vision must express a genuine disgust for Washington politics, but be devoted to eliminating the corrupting power of the wealthiest one percent, rather than scapegoating immigrants and people of color.

In the short run, this will require pressuring fickle and opportunist politicians to stubbornly oppose and filibuster White House extremism, even at the risk of being labeled obstructionist by critics. In the longer term, it will involve creating an effective opposition in the Democratic Party to ensure that Trump’s next opponent will not be another establishment candidate, deeply compromised by ties to corporate America. Rather, this opponent must be someone who can genuinely speak to the disenfranchisement and frustration that many in this country feel.

In choosing targets such as Schumer, organizers recognize that, in the next few years, direct opportunities to win concessions from the Trump-Pence administration will be slim. In contrast, social movements will have a much greater role in rallying and reorganizing the opposition. They have the power to tarnish politicians who once denounced Trump but now say they want to cut deals with the president. And they can work — at local, state and national levels — to elevate insurgent challengers willing to pursue a different type of politics.

Learning from the anti-war movement under Bush

The anti-war movement in the 2000s under George W. Bush provides an important example of a mass mobilization that arose in a time of Republican control, when the prospects of directly influencing policy appeared remote. Because of this, it offers lessons in how a movement can have much greater impact in affecting Democratic politics than in changing White House behavior.

Movements against the current regime do well to not merely study the example, but to avoid replicating its shortcomings. The challenge they face is making sure that the political candidates empowered by organized anti-Trump activity cannot simply co-opt the energy of the movement, but rather represent a true shift in power away from the corporatist center.

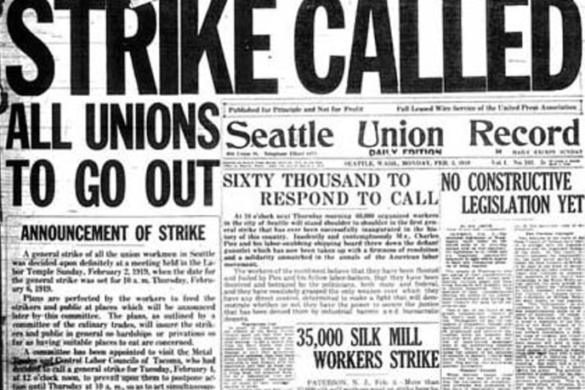

In 2003, as President George W. Bush and his cabal of neoconservative advisers were determinedly steering the United States towards new wars in the Middle East, an impressive number of people rallied in a reinvigorated anti-war movement. Its defining protest took place on February 15, 2003, when upwards of 10 million people in 600 cities around the world came out for what was possibly the largest day of coordinated international protest in world history.

Yet today, this anti-war movement is typically viewed as a failure, for a simple reason: critics point out that it did not succeed in stopping the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq.

Although this point is obviously true, the narrative of failure deserves critical scrutiny. A large number of those who turned out to protest in early 2003 were well aware that stopping the administration’s much-desired invasion would be next to impossible. Indeed, they were already planning protests to take place immediately if and when the war commenced. Organizers pursued this activity not so much with a naive hope of pulling off a miracle, but rather with more sophisticated goals in mind: They were determined that the war, from the start, should be viewed by the public as a reckless and destructive endeavor, that the official justifications for invasion be exposed as lies, and that, as much as possible, popular opposition constrain the wider foreign policy agenda of the neoconservatives.

Given that the Bush-era militarists were interested not only in overthrowing Saddam Hussein, but also bombing countries such as Syria and Iran, the anti-war movement served a critical function in limiting the wave of patriotic fervor that typically accompanies the start of a new war and quickly putting the neocons on the defensive. In the end, these hawkish advisors saw their credibility swiftly plummet, and anti-war opposition helped render Bush a lame duck for the majority of his second term in office.

But arguably the most profound effect of the anti-war movement was not felt inside the Republican White House, but instead inside the Democratic Party. This dynamic is noteworthy for anti-Trump protesters. The movement succeeded in turning the party’s base against Democrats who had supported Bush’s invasion, and it made strong anti-war stances into the pragmatic position for politicians concerned about their political futures.

Before it commenced, a large number of Democratic officials were fully complicit in facilitating the Iraq War. In the fall of 2002, a majority of Democratic Senators — 29 out of 50 — joined the Republicans in voting to empower Bush to launch an invasion. Mainstream Democrats such as Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden likely believed that a “no” vote would expose them to criticism of being unpatriotic or soft in the “war on terror,” and that an anti-war stance would come back to haunt their future political prospects.

Grassroots organizing played a vital role in turning this reasoning into a huge miscalculation — making opposition to Bush the safe bet for Democrats and ensuring that centrists such as Clinton would grow to regret their Iraq War votes.

In the 2004 Democratic presidential primary, Howard Dean rose from obscurity to seriously challenge for the nomination, based on strong support from anti-war voters and activists in the party base. To fend off Dean’s challenge, candidates such as John Kerry struggled to present themselves as leaders who had actually opposed Bush’s war from the start. Later, in 2007, the same constituency propelled a little-known Barack Obama to prominence as an anti-war candidate, with more established politicians such as Hillary Clinton and John Edwards scrambling to explain away their earlier hawkishness.

By this time, the political wisdom that pro-war stances by Democratic politicians were necessary to safeguard their political futures had been completely reversed. Like many historical shifts, this might seem inevitable when viewed in hindsight, yet it was anything but.

Examined through the simplistic lens of “did the movement stop the invasion of Iraq?” the anti-war movement may be seen as a failure. Yet it deserves significant credit for convincing reluctant politicians to begin standing up to Bush, redefining political common sense within the Democratic Party and coalescing a powerful constituency for peace.

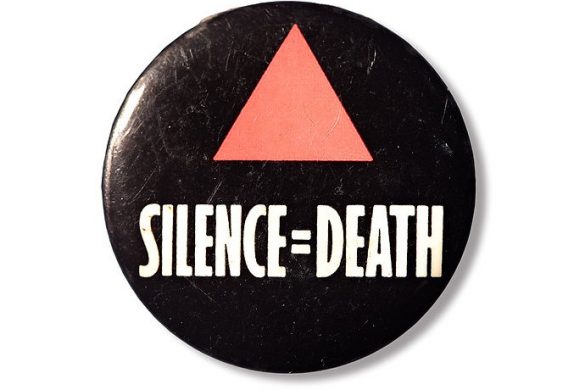

Blocking a hateful agenda

Of course, many progressives were hardly satisfied with President Obama’s handling of foreign policy once he was elected. And this points to the need to build oppositional movements that cannot be co-opted by politicians willing to adapt themselves to the norms of Beltway “realism.” Progressives face the challenge of building a base of insurgent challengers who can articulate a wider vision of social, racial and economic justice. Fortunately, the revived movement organizing over the past five years (from Occupy to the Movement for Black Lives and beyond), along with the unexpectedly strong primary run of Bernie Sanders, have created a more robust basis for pushing forward a proactive program than existed during the Bush years.

Currently, the stage is set for a battle over the future of the Democratic Party. Schumer did not back down in his bid for leadership and has now become Senate Minority Leader. Yet, at the same time, Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, representing the populist branch of the party, were also named to leadership positions, Sanders as the party’s new “Chair of Outreach” and Warren as party vice-chair. For those committed to combating corporate control of the Democrats, these latter appointments — along with the prospective appointment of Keith Ellison to head the Democratic National Committee — represent first steps in an effort that will only intensify in the next two years. This fight will take place not only with regard to federal politics, but also at the state and local levels.

Whatever one makes of the prospects for realignment within the Democratic Party, there is little question for progressives that politicians prone to conciliation must be compelled to take steadfast stands to block Trump’s extremist agenda, even if the right denounces these stands as obstructionist.

In recent years Republicans, pressured by a Tea Party base, were willing to relentlessly stonewall to stop Obama, taking the unprecedented step of never even holding hearings on the president’s latest nominee to the Supreme Court. In contrast, some Democrats who have a long history of triangulation are already expressing a willingness to work with Trump. If the incoming president was truly anti-establishment, seriously willing to take on Wall Street, end the rule of the rich over our democracy, and uphold Constitutional values of equal rights, religious tolerance and free speech, there might be grounds for such cooperation. Instead, Trump has given every indication that he will fill his administration with corporate lobbyists and advocates of hate. Any legislation he presents as an overture toward bipartisanship — on infrastructure, for example — is certain to be loaded with poison pills that damage vulnerable communities.

In this context, politicians who play along with the White House fall into a trap: They grant Trump the opportunity to present himself as the man who made Washington work, instead of forcing him to bear the burden of a failure to govern.

Social movements have every reason to oppose this tendency, to create the political will to filibuster, and to bolster politicians who will break with the discredited neoliberal center. This involves an approach that does not spare ostensibly friendly insiders. As #AllOfUs has already demonstrated, fighting Trump may often mean targeting the Democrats.