By Mark and Paul Engler

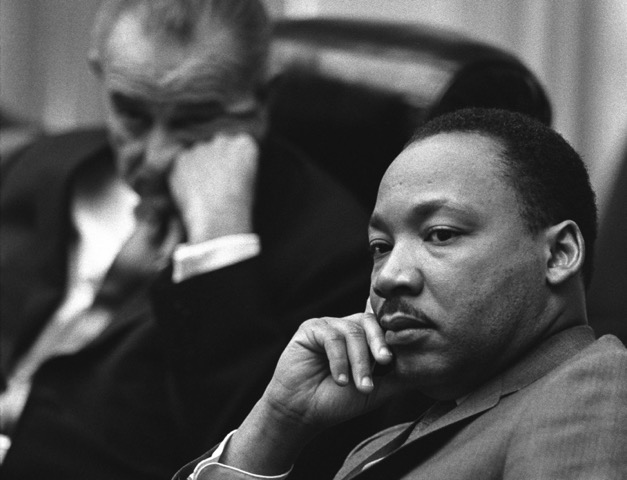

(Published on January 18, 2016 by Rolling Stone. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Early in 1967, America was mired in an escalating war in Vietnam, presided over by President Lyndon B. Johnson. A collection of liberal leaders including anti-war Yale chaplain William Sloane Coffin, prominent socialist Norman Thomas, and future Congressman Allard Lowenstein were determined to recruit a serious anti-war candidate to challenge Johnson in 1968.

They believed they had the perfect prospect: Martin Luther King Jr.

By 1967, King had gained stature as the nation’s preeminent civil rights leader. Against the advice of many, he was also speaking out against the Vietnam War, arguing that costly and immoral interventionism abroad was hindering progress toward racial and economic justice at home.

The liberal leaders, sensing that King could galvanize voters looking for an outside crusader, proposed that he run a third-party campaign with Dr. Benjamin Spock, the famed pediatrician and anti-war critic, as his running mate.

These leaders were not the only ones hoping for a run by King. When the civil rights champion spoke at Berkeley in May 1967, students held homemade signs that read, “King / Spock in ’68.”

King considered the prospect of a presidential bid, but he ultimately decided against it. His reasons why reflect an understanding of how social change happens that differs markedly from that of many current presidential candidates—perhaps most notably Hillary Clinton.

A Different View of Power

On August 11, 2015, faced with the prospect of having a campaign appearance in New Hampshire protested by Black Lives Matter activists, Clinton agreed to meet demonstrators backstage. In an exchange that lasted more than fifteen minutes, the former secretary of state pressured activists to focus on specific policy proposals that might be viable in Congress or in the courts. She argued, “I don’t believe you change hearts. I believe you change laws, you change allocation of resources, you change the way systems operate.”

Her position was consistent with her career of pressing for reform (or failing to do so) within the confines of beltway debate. Essentially, she told the activists that they needed to work within the system to get anything done.

This is not an uncommon position. Yet King had a very different perspective, one consistent with the field now known as “civil resistance.” Drawing from the work of theorists such as Gene Sharp, scholars in this field argue that power is more widely distributed than is typically believed—and that CEOs, generals, and senators do not hold all the cards. Even entrenched dictators rely on the compliance of the people in order to maintain power. If a sufficient number of people choose not to cooperate with an existing order, the standing of these leaders crumbles.

Civil resistance movements can look beyond a “transactional” model of politics that attempts to exact small gains based on conventional wisdom about what is feasible within Washington. Instead, through disruptive and dramatic protest, they alter the political climate and create new possibilities for change–turning impractical demands into urgent priorities.

The recent victory around gay marriage is a prime example. This win came about not through great acts of political leadership from officials in high office. Rather, it was secured when courts of law ratified what campaigners had already won in the court of public opinion. Politicians—Hillary Clinton included—”evolved” in their stances on the issue only after it had become clear that public opinion had decisively shifted.

A Conversion to Nonviolent Direct Action

Early in his career, Martin Luther King Jr. might have been sympathetic towards Clinton’s view of how change occurs. In 1955 and 1956 he had been thrust, almost by accident, into the leadership of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. In the years that followed, his newly formed Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was tentative, and it might well have stuck with a conventional strategy of lobbying and legal action. It was the 1960 student lunch-counter sit-ins and 1961 Freedom Rides that pushed King toward adopting nonviolent direct action as his primary tool of resistance.

In Birmingham, Alabama in the spring of 1963 King, his advisors, and local activists set out to consciously engineer a nonviolent uprising that could “create such a crisis and establish such creative tension” that the injustice of segregation would be forced onto the national stage. Their success changed King’s vision of what could be accomplished outside the limits of formal politics.

A traditional view of power gives credit for social change to the political leaders who pass landmark legislation. This perspective sees the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as foremost the result of the legendary arm-twisting of President Lyndon Johnson. During her 2008 campaign Clinton herself embraced this view, emphasizing Johnson’s role. In this case, it created a scandal for her, as defenders of the civil rights movement charged Clinton with advancing a blinkered view of history.

In fact, mass noncompliance in Birmingham and beyond convinced politicians who would have preferred to drag their feet that inaction was no longer a viable option. As historian Adam Fairclough writes, it convinced Attorney General Robert Kennedy that “the federal government, unless it adopted a more radical policy, would be overwhelmed.”

Fairclough further adds, “Birmingham, and the protests that immediately followed it, transformed the political climate so that civil rights legislation became feasible; before, it had been impossible.”

Beyond Partisan Politics

Through the end of his life, King remained committed to using social movement pressure to force officials to act in ways they would have otherwise avoided.

Seeking to quell speculation about a King/Spock ticket, the SCLC leader called a meeting with reporters in April 1967 and announced that he was not interested in running. “I have come to think of my role as one which operates outside the realm of partisan politics,” King said.

Opting against a presidential run, he instead launched the “Poor People’s Campaign,” which proposed a major wave of disruptive protest in Washington, DC, designed to compel action around economic inequality. “We believe that if this campaign succeeds, nonviolence will once again be the dominant instrument for social change—and jobs and income will be put in the hands of the tormented poor,” King stated in 1968. Tragically, an assassin’s bullet prevented him from bringing the mobilization to fruition.

Nevertheless, movements such as Black Lives Matter and the Fight for $15 are now carrying on in King’s transformative tradition, helping to set the agenda of debate for the Democratic contest.

In choosing the path of a career politician, Bernie Sanders has opted for a different route than King. But he shows more understanding than most about how social movements can reshape the terrain of the politically possible. Calling for a “political revolution,” Sanders has argued that “no matter who is elected to be president, that person will not be able to address the enormous problems facing the working families of our country.” Instead, grassroots movements are needed to change the focus on the national discussion.

Sanders has already accomplished far more than most professional political observers had predicted. But it will take much more than an energetic primary run to make a “political revolution” a reality. King’s vision of nonviolent protest in Washington, DC, massive and confrontational, may yet be necessary to save American democracy.