By Mark and Paul Engler

(Published on January 18, 2016 by Salon. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Tony Webster)

Martin Luther King Jr. is often held up as one of the leading pacifists in American history—a moral voice who called for the nation to come together across lines of racial division.

Yet, while this vision of King as a peaceable and unifying figure may be comforting, it is incomplete at best and in many ways misleading.

In its time, King’s use of nonviolent resistance generated a nearly unending stream of controversy. And in this era of Black Lives Matter, it is critical to remember that, far more than a serving as a peacemaker, King was an advocate of disruption.

Looking back from the safe remove of history, it can be easy to imagine that landmark social and political causes of the past—whether they involved ending slavery, securing the franchise for women, or establishing standards of workplace safety—were popular and widely celebrated. But the truth is that these issues generated tremendous acrimony. In promoting them, activists had to make the difficult decision to invite division and hostility before they achieved their most impressive results.

King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) often drew criticism not only from defenders of segregation, but also would-be allies who believed the protests the organization helped lead were unduly abrasive and ultimately counter-productive. In this way, King bears much in common with the #BlackLivesMatter activists who are currently being attacked for perceived impatience and incivility in promoting their cause.

The Peril of Lukewarm Support

Today, groups ranging from climate change divestment activists on campuses, to immigrants’ rights advocates, to Black Lives Matter protesters are constantly told that they are going about things in the wrong way—particularly if they dare to undertake actions that are disruptive. Yet, as we argue in our new book, This Is an Uprising, disruption is not incidental to the success of protest movements—it is essential. As Martin Luther King Jr. discovered, confrontational action may make some supporters uncomfortable, but it nevertheless provides crucial force in leveraging change.

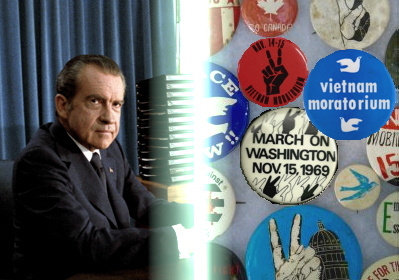

In November 2015, after 24-year-old Minneapolis resident Jamar Clark—an unarmed black man—was shot and killed by police, Black Lives Matter activists set up an encampment at the Police Department’s Fourth Precinct headquarters. U.S. Representative Keith Ellison, widely known as a champion of progressive causes, initially expressed support for the protesters. However, after five activists were shot by a group of white supremacists in front of the camp, Ellison joined Mayor Betsy Hodges and a variety of other local officials in releasing a joint statement calling for “ending the occupation at the Fourth Precinct immediately.”

In a social media exchange with Black Lives Matter activists that followed, Ellison invoked King to defend his position against the protest encampment. He tweeted “Pls read Letter From Birmingham Jail. MLK didn’t just sit on Edmund Pettus Bridge. Moved to 1965 Voting Right Act.”

Although Representative Ellison possesses a strong record on civil rights, in this case Black Lives Matter activists were correct to charge that Ellison was getting King’s famous letter exactly wrong.

Today, King’s 1963 “Letter from Birmingham City Jail” is viewed as an eloquent explanation of the aims and methods of the struggle against segregation. It stands as one of the most significant and closely studied essays written by one of America’s national heroes. It is less commonly remembered, however, that King did not write the letter as a response to racist opponents. Instead, he was addressing would-be supporters who criticized the movement’s approach as too uncompromising and impetuous.

On April 12, 1963, during the second week of mass protests in Alabama, King, along with his close friend Ralph Abernathy and forty-six other demonstrators, was arrested for kneeling down in prayer in front of Birmingham’s City Hall, a clear violation of the recently instated injunction against public demonstrations in the city. The day after the arrest, eight clergymen, prominent white liberals from the state, published an open letter in the Birmingham News voicing their opposition to the direct action tactics being used by King, the SCLC, and the local Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights.

Uncomfortable with the heedless confrontation of the civil rights campaign, the ministers wrote, “We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized. But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.”

“When rights are consistently denied,” the ministers further argued, “a cause should be pressed in the courts and negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets.”

Having been placed in solitary confinement, King was unnerved by the isolation of imprisonment. Yet when he was permitted news from the outside and he saw the ministers’ open letter, he focused his attention. He promptly began writing a reply on whatever scraps of paper he could find.

King charged that the ministers preferred order to justice. “You are exactly right in your call for negotiation,” he wrote. “Indeed, this is the purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and establish such creative tension that a community that has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront an issue.”

Due to the previous intransigence of local powerbrokers, King argued, civil rights protesters had little choice but to take up direct action “whereby we would present our very bodies as a means of laying our case before the conscience of the local and national community.”

Although the letter started polite, King soon expressed a righteous frustration with ostensible allies who devoted themselves to criticizing the movement. “Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will,” he wrote. “Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”

Pressure, Not Proposals

Black Lives Matter activists were right in their contention that Ellison and other members of Minnesota’s political establishment—in taking the stance of those “who [agree] with the goal, but not the tactics” of protest—were adopting the role of King’s interlocutors.

A common complaint of such critics is that those employing nonviolent resistance today do not focus narrowly enough on legal and legislative plans that might be feasibly implemented by those in power. Ellison’s mention of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and his claims that Black Lives Matter activists should train their attention on the grand jury proceedings in the Jamar Clark case, reflects this bias.

Yet this is a misreading of what made the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s effective in the first place. As historian and King scholar Adam Fairclough argues, Martin Luther King Jr. “maintained to the end of his life that it was far more important to dramatize the broader issues and generate the pressure for change than to draft precise or specific legislation. The exact manner in which the federal government responded to the problem of discrimination did not greatly concern SCLC. What mattered was that its response should be determined, vigorous, and thorough. The administration responded to pressure, King reasoned, not proposals.”

Nor did King believe that the need for disruptive protest had grown any less urgent following the passage of major civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965. In a lecture delivered in late 1967—later collected in a book entitled The Trumpet of Conscience—King argued, “There is nothing wrong with a traffic law which says you have to stop for a red light. But… when a man is bleeding to death, the ambulance goes through those red lights at top speed.”

Despite advances such as the Voting Rights Act, King stated, “by now it is obvious that new laws are not enough.” He argued, “There is a fire raging now for the Negroes and the poor of this society,” and what was needed was a strategy of “massive civil disobedience” that would be “at least as forceful as an ambulance with its siren on full.”

To address this emergency, King intended to lead a Poor People’s Campaign of nonviolent direct action in Washington, DC in the summer of 1968. Sadly, he was assassinated before he could carry this out. In many respects, the Black Lives Matter movement is taking up the unfinished business of the 1960s—and it is using the same tactics of nonviolent of confrontation that King envisioned in order to create the pressure needed for change to take place.

No doubt, as protests continue in the future—around urgent issues such as racial justice, climate change, economic inequality, and the corporate hijacking of democracy—we will again hear a familiar refrain: that activists are unduly divisive; that their demonstrations are untimely and counterproductive; that they should show more patience in letting the system respond; and that they need to be more pragmatic in laying out legislative remedies.

We should see these criticisms as a natural outgrowth of activists’ decision to follow the path of Martin Luther King Jr.—to take up a legacy of activism that was effective, but that was first disruptive.