How creating a “healthy ecology of change” can help propel social movements.

By Mark Engler and Paul Engler

(Published on March 17, 2017 in Waging Nonviolence)

At the end of 1930, India was experiencing disruption on a scale not seen in nearly three quarters of a century — and it was witnessing a level of social movement participation that organizers who challenge undemocratic regimes usually only dream of achieving.

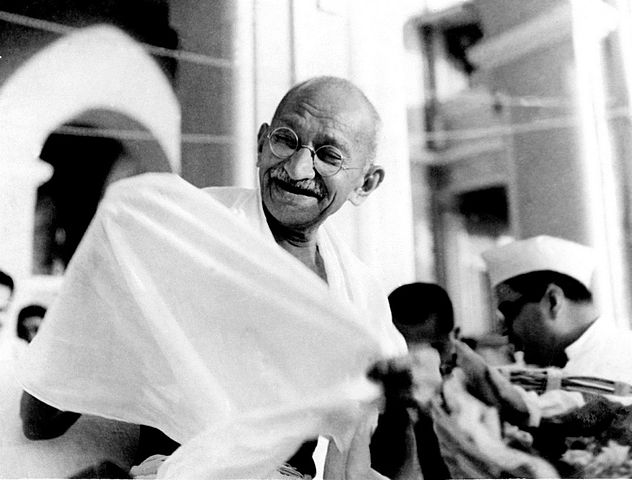

A campaign of mass non-cooperation against imperial rule had spread throughout the country, initiated earlier that year when Mohandas Gandhi and approximately 80 followers from his religious community set out on a Salt March protesting the British monopoly on the mineral. Before the campaign was through, more than 60,000 people would be arrested, with as many as 29,000 proudly filling the jails at one time. Among their ranks were many of the most prominent figures from the Indian National Congress, including politicians that had once been reluctant to support nonviolent direct action.

Not only were Indians illegally producing salt and staging blockades of government salt works, but, as the effort grew, the campaign adopted a rich array of additional tactics. Hundreds of thousands of villagers refused to pay land and timber taxes. Civil servants resigned from government, with as much as a third of local officials in one district of Gujarat declaring that they would leave their posts. And activists maintained an organized boycott of British imports to India. In the words of one historian, major textile centers including Calcutta, Bhagalpur, Delhi, Amritsar and Bombay, “came to a virtual standstill for part or most of 1930 as a result of [strikes], picketing and self-imposed closures by businessmen.”

Observers near and far could sense the historic magnitude of the moment. In England, Winston Churchill, then a conservative member of Parliament, railed furiously at what he perceived as his government’s incompetence in properly defending the empire. British officials within India were similarly distressed. Sir Frederick Sykes, the governor of Bombay, wrote to his superiors in May 1930: “It is now necessary frankly to recognize the fact that we are faced with a more or less overt rebellion … and that it is supported either actively or passively by a very large section of the population. We have, for one reason or another, practically no openly active friends.” One police commander described his district as: “virtually in a state of war for a substantial part of the year.”

How did the Indian independence movement get to this point? What type of organizing had allowed for this uprising to take place? What strategy had led to such widespread and coordinated disobedience?

In truth, it was not one strategy, but the combination of several. And a large part of the political genius of Mohandas Gandhi lay in his ability to bring these disparate strategies together.

For people seeking to generate change today, the landscape of social movements can appear fragmented and confusing. Responding to the myriad challenges of racial oppression, economic exploitation and environmental catastrophe, different groups pursue widely varying organizing strategies. Some people work to create mass mobilizations — actions such as the Women’s March, Occupy Wall Street, or large immigrant rights protests — that draw significant public attention, but that can fade away quickly. Others focus on the slow-and-steady work of building long-term institutions, such as unions or political parties. Still other groups foster countercultural communities and alternative institutions outside of the mainstream. Often, there is little contact between groups employing different strategies — and little sense of common purpose.

However, these different efforts need not see themselves at odds with one another. Movements function best when they recognize diverse roles and find ways to employ the contributions of each in constructive ways. In fact, this can be a key to success.

Although his organizing against British rule in India began a full century ago, Gandhi encountered many of the same divisions that we continue to see resurfacing in modern politics. Because of this, his ability to foster and nourish a rich social movement ecosystem — in which different approaches to change each helped to advance an overall anti-imperialist effort — offers intriguing lessons for today.

Bringing together organizing traditions

Gandhi is one of the most revered public figures of the 20th century. Yet, for all of his renown, Gandhi’s actual strategies for promoting social change in India are much less known. Some people think of him as a spiritual figure who led through moral persuasion alone. Others have heard of the most famous acts of civil disobedience undertaken by him and his followers, protests that have been celebrated widely and dramatized in Hollywood movies. Still others picture him as a political figure, sitting at the negotiating table across from officers of the British Empire.

All of these ideas reflect aspects of Gandhi’s political life. However, each portrait by itself is incomplete.

Gandhi’s methodology for bringing about social transformation was more interesting than any one of these facets suggests. What makes him such a unique figure to examine within the history of social movements is his ability to bring together a variety of different types of organizing. Gandhi was able to cultivate what can be called a healthy “ecology of change,” in which groups with diverse theories and practices for changing their society could each expand the capabilities of the movement as a whole.

In particular, he united three strains of activity — strains which parallel those present today in the U.S. and beyond: First, large-scale mobilizations that employed nonviolent direct action (what Gandhi called satyagraha). Second, efforts to build a lasting organizational structure (the Indian National Congress) that could influence dominant institutions. And third, the creation of alternatives outside of the mainstream (such as Gandhi’s ashrams and the “constructive program”).

Although these three different approaches for fostering progress — mass protest, structure-based organizing, and the creation of alternatives — have been present in many other countries in many different time periods, it is rare when the three approaches collaborate in the service of a unified social movement. Gandhi served as a bridge between these different orientations, providing an exceptional model of how movements can benefit when different strategies come together.

To appreciate Gandhi’s rare talent at bridging these worlds does not require putting him on a pedestal. While it may come as a surprise to those who regard him as an unquestioned saint, Gandhi has always been mired in controversy. The soundness of his various religious and social prescriptions, along with the merit of his countless strategic decisions, were the subject of constant debate even within his own lifetime — and the debates have continued since his death in 1948. Yet, even given the various contradictions and contentions surrounding Gandhi’s career, we can draw valuable insights from the growth of the Indian independence movement in his time and its success in elevating anti-imperialist agitation against British rule to historic levels.

Satyagraha: igniting a mass protest

The first type of activity that Gandhi promoted is perhaps his most renowned: He was famous for creating campaigns of mass disruption that would draw in many thousands of participants, spread over large areas, and force an issue to the fore of political discussion. Gandhi referred to this method of mass mobilization as satyagraha, or the application of “truth force.” Throughout his life, Gandhi led more than a half dozen major satyagraha campaigns. Undertaken over a period of four decades, these began with his initial experiments in civil disobedience and noncooperation in South Africa and culminated in drives that affected the whole of India.

The first mobilizations in India involved regional campaigns of strikes and protests by farmworkers in 1917 in Bihar and 1918 in Gujarat. In the latter case, farmers collectively refused to pay land taxes even in the face widespread arrests, beatings and confiscation of farmland. After five months, the government relented and returned land, released prisoners and eased taxes.

While such early drives were largely contained to local areas, the satyagrahas grew into disruptive campaigns with much larger scope. Today, as in Gandhi’s time, when mass protests grab headlines and send thousands into the streets, they are regularly described as “unplanned,” “emotional” and “spontaneous” uprisings. Many observers do not think that such upheavals can be planned at all, but rather are the product of the historical zeitgeist. Gandhi offered a different view. He argued that moments of whirlwind activity could be engineered by skillful practitioners. An influential early study of Gandhian civil resistance noted that “Satyagraha, as applied socio-political action, requires a comprehensive program of planning, preparation and studied execution.” Indeed, Gandhi’s refinement of this art — the strategic use of unarmed uprising — is one of his great contributions to social movement history.

Gandhi’s first nationwide satyagraha was the 1920-22 drive known as the Non-Cooperation Movement. This campaign unfolded through a series of escalating actions. Historian Perry Anderson describes four levels of disruptive activity: “First, renunciation of all titles and honours conferred by the British; next, resignations from positions in the civil service; then, resignation from the police and army; finally, refusal to pay taxes.” Following Gandhi’s announcement of the strategy in August 1920, the drive quickly took hold. “The campaign electrified the country,” Anderson notes, “drawing in social layers and geographical regions hitherto untouched by nationalist agitation[.]” Historian Judith Brown adds, “Men and women, old and young, townsman and rustic, could choose the action appropriate to them, from attending a meeting to closing a shop, staying away from classes, or persuading local shopkeepers to stop selling foreign cloth and liquor.”

The impact could be felt across an expansive area. Hindi poet Rambriksha Benipuri famously remarked, “From the time I have been aware, I have witnessed various movements; however, I can assert that no other movement upturned the foundations of Indian society to the extent that the Non-Cooperation Movement did.”

By early 1922, British administration had been disrupted but not disabled, and noncooperation leaders determined that the movement was ready to begin a tax strike. However, only four days after announcing this escalation, Gandhi controversially decided to call off the Non-Cooperation Movement altogether following an outbreak of violence in the northern town of Chauri Chaura. Gandhi subsequently spent two years in a British jail for promoting seditious activity. While the strategic wisdom of curtailing the campaign was hotly debated among supporters and detractors alike, what is not in question is that the drive successfully translated the principles of satyagraha from its regional applications in Bihar and Gujarat to an India-wide movement. In doing so, it set the stage for an even larger wave of mass civil resistance: the Salt Satyagraha.

Commencing in March 1930, the Salt Satyagraha began with a 200-mile march by Gandhi and his supporters to the coastal city of Dandi, and it expanded quickly from there. “The march generated great India-wide publicity,” Brown writes, and soon millions more joined the satyagraha. Although British authorities brutally repressed protests and made tens of thousands of arrests nationwide, resistance continued month after month. Reflecting on the breadth of mobilization, nationalist leader and future Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru later stated, “It seemed as though a spring had suddenly been released.”

After nearly a year of protest, sensing that the momentum of the campaign was abating, Gandhi brokered a settlement with the British Viceroy, Lord Irwin. While political insiders debated the value of the short-term gains secured in the compromise, the Indian public recognized that the Salt Satyagraha had dealt a significant blow to British prestige in India — a sentiment echoed by hardline imperialists in London, who regarded the settlement as a fatal blunder for the empire.

Building a structure for opposition: the Indian National Congress

Even as Gandhi led dramatic mass protests, he also contributed to building up a stable, long-term organization that could serve as an institutional body to represent the independence movement. That organization was the Indian National Congress. Founded in the 1880s, the original purpose of Congress was to foster the greater influence of Indian elites in the British-controlled government. After his return to India in 1915, Gandhi worked to change the organization’s composition and outlook, and in the following decades Congress grew steadily larger and more antagonistic toward the British. By 1930, the organization was advocating for full national independence and expulsion of the British Raj. In time it would become the ruling party of the world’s largest democracy. On August 15, 1947, Nehru, one of Gandhi’s top lieutenants, took office as India’s first prime minister, representing the dramatic transformation of Congress from a small dissident group to a insider party holding the reins of state power.

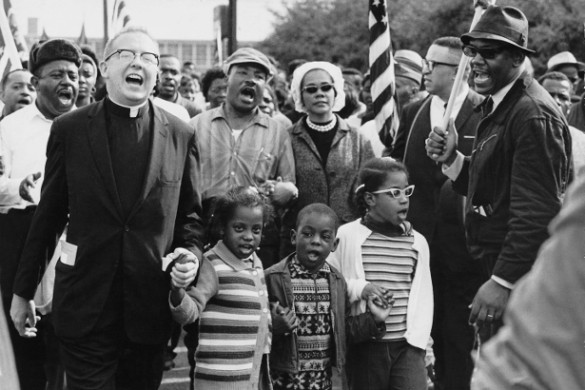

The gradual growth of Congress over the span of decades was akin to “structure-based” organizing in other parts of the world, such as the formation of social-democratic parties in Europe. In the U.S. context, we can see examples of structure-based organizing in the formation of major labor unions and in Saul Alinsky’s model for building community-based organizations that can leverage the power of their members over time. With reference to the U.S. civil rights movement, Gandhi’s satyagraha campaigns could be likened to high-profile drives such as the Freedom Rides or the Birmingham campaign, while the Indian National Congress bore more in common with durable membership organizations like the NAACP.

Gandhi’s involvement in the leadership of the Indian National Congress was episodic, and he would sometimes withdraw for long periods of time to focus on other aspects of his work. He held official positions only for relatively short stretches, and he went so far as to resign his party membership for a time, starting in 1934, after growing frustrated with internal politicking. Yet whatever his formal role at a given moment, Gandhi served as a key figurehead of Congress for nearly three decades, and his interventions played a decisive role in shaping the organization’s development. Even critics of Gandhi, such as Perry Anderson, acknowledge that, in the historian’s words, Gandhi “was a first-class organizer and fundraiser — diligent, efficient, meticulous — who rebuilt Congress from top to bottom, endowing it with a permanent executive at the national level, vernacular units at the provincial level, local bases at the district level, and delegates proportionate to the population, not to speak of an ample treasury.”

Rajendra Prasad, a longtime party leader, recalled several decades later that, prior to Gandhi’s involvement, “Congress had aroused and organized national consciousness to a certain extent; but the awakening was confined largely to the English-educated middle classes and had not penetrated the masses.” Historian Judith Brown is more blunt: the Congress of 1915, she writes, was little more than a “shambling debating society,” largely confined to major urban areas and possessing scant grassroots infrastructure; over the next decade, Gandhi’s organizing talents helped transform it into a “formidable national organization and fighting force.”

Among other activities, Gandhi authored a new organizational constitution that established a more representative governance structure for Congress and substituted Hindi for English as the language of party business. It also steeply reduced membership dues so that, as playwright, author, and first-hand observer Krishnalal Shridharani wrote in 1939, “the poor had as much opportunity to join as the rich.” Gandhi relentlessly traveled to different regions to cultivate relationships, solidify support for his program, and build up local party infrastructure. By 1922, there were 213 District Congress Committees, covering the great bulk the country that was under direct British administration. Shridharani estimated that by 1930 one out of every three villages had a Congress office. Gandhi’s exceptional fundraising abilities helped to support this growth.

In a heterogeneous India, rife with divisions of class, caste, religion, and geography, most organizations represented limited, sectarian constituencies. Congress made significant strides toward defying this trend, uniting rural and urban, educated and uneducated, and bridging large geographical expanses. Maintaining participation and shoring up the party’s local infrastructure was a continual challenge, and Gandhi’s hopes of bringing together Hindus and Muslims met with very limited success. Nevertheless, Judith Brown writes, by the early 1920s Congress had established itself as “the only organization with any realistic claim to be the mouthpiece of a nation.”

Living the alternative: the constructive program

In addition to the mass satyagraha campaigns and his structure-based organizing through the Indian National Congress, Gandhi was also active in the creation of alternatives, or what has sometimes been called “prefigurative politics.” This aspect of his work is evident in statements from Gandhi including his contention that “The best propaganda is not pamphleteering, but for each one of us to try to live the life we would have the world live.”

For Gandhi, the idea of India gaining independence was more than a political goal; it involved changing one’s way of life. His anti-imperialism did not involve merely having Indian elites take over national rule from the British. It also included a rejection of Western conceptions of civilization and modernity, against which he juxtaposed a vision of reinvigorated Indian village life. He saw his efforts to build alternative communities and counter-cultural institutions as an essential component of the overall push for swaraj, or freedom. Historian Dennis Dalton writes that, while more instrumentally focused Congress politicians understood swaraj in narrow terms, “Gandhi interpreted the word to mean freedom in two distinct senses: the ‘external freedom’ of political independence and ‘internal freedom,’” which required a more personal process of decolonization and the pursuit of social transformation outside the realm of formal politics.

Pursuing swaraj, then, was not just a matter of pushing for legal reforms. Rather, Gandhi spent much of his time working on what he called the “constructive program.” In the words of author and theorist Gene Sharp, the constructive program was an attempt “to begin building a new social order even as the old one still exists,” with decentralized cooperatives “functioning independently of the state and other institutions of the old order.” Gandhi’s vision for the constructive program included many overlapping activities: he advocated spinning of hand-woven cloth (or khadi), the expansion of village industries such as soap- and paper-making, and enhanced public sanitation and personal cleanliness. He pushed for simplicity in lifestyle, improved education, cultural practices that rejected established divisions between Hindus and Muslims, and the end of “untouchability.”

As a result of these efforts, many in Gandhi’s time viewed him less as a political leader than a religiously-driven lifestyle advocate. In his published writings, he frequently took up issues of diet and hygiene, concerning himself with matters such as the best way to make an affordable, effective and reusable toothbrush out of commonly available twigs. Needless to say, these were far from the core concerns of organizers in Congress, who focused on constitutional questions of how India would secure self-governance.

Gandhi’s vision of the constructive program was most fully put into practice in his ashrams, or intentional communities. Over the course of his life, Gandhi established and lived in a series of spiritually-oriented retreats, including the Sabarmati Ashram in Gujarat (where he lived from 1917-1930) and the Sevagram Ashram in Maharashtra (where he lived from 1936-1948). In each case, hundreds of devoted followers lived in community with Gandhi and his lieutenants, adhering to a strict regimen of personal discipline, prayer and public service.

Historians Judith Brown and Anthony Parel write that Gandhi considered the ashrams to be his “best work and [the place] where he tried to work out the core elements of his spiritual vision of the good human life in the pursuit of Truth.” Elsewhere, Brown writes that, for Gandhi, “they were places akin to laboratories where he could attempt to solve in microcosm problems that affected India on a much larger scale.” Regardless of the success or failure of Congress’ political demands on the British, ashram members were living their vision of swaraj in communities that reflected the ideals of local autonomy and decentralized government.

Ashram members lived in voluntary poverty. Among other aspects of communal life, they possessed limited material belongings, ate simple vegetarian meals, slept in collective residences, took vows of sexual restraint, and performed manual labor. They shared in domestic chores, no matter how menial, without regard to one’s class background or caste position. Moreover, they devoted themselves to serving nearby villages through medical relief, hygienic work, instruction in the hand-spinning of cloth and other crafts, and education against untouchability.

The ashrams also provided a base from which Gandhi and his followers developed a wider network of political volunteers and social workers. Early chronicler Shridharani argued in 1939 that this dedicated cadre of volunteers served as “the nuclei of the economic and spiritual regeneration of India’s countryside.” The constructive program reached beyond the ashrams in other ways as well. As one example, the All-India Spinners’ Association, dedicated to spinning khadi cloth and providing employment to Indian farmers during off-seasons, was active in some 15,000 villages and employed more than 350,000 spinners and weavers in 1942. Gandhi called on Indians throughout the country to boycott imported cloth and take up spinning as a method of noncooperation with British industry. In the words of writer Ved Mehta, he made “‘spinning wheel’ a byword for economic independence and nonviolent revolution.”

Toward a healthy movement ecosystem

The three distinct approaches to pursuing social change reflected in Gandhi’s diverse activity — the use of mass protest, structure-based organizing and creating alternatives — are not unique to the drive for Indian independence. Instead, they appear in many different social movements, across continents and time periods. But because these distinct organizing traditions are based on different theories of change, they often find themselves in conflict with one another.

One can find many examples of these tensions. A well-known saying to emerge from the community organizing tradition of Saul Alinsky was “Build organizations, not movements.” Here, suspicion of “movements” reflected a skepticism of mass mobilizations that seemed to burst suddenly onto the political scene but then to fade out just as rapidly. Likewise, in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, friction between “organizing” and “mobilizing” produced heated internal movement debates among groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or SCLC.

While mass mobilization and structure-based organizing are sometimes at odds, both approaches can be in tension with groups focused on “living the alternative.” Organizers trying to directly contest the power of capital or of the state are often dismissive of activists who are more interested in creating countercultural communities that sidestep currently dominant institutions. Sociologist Wini Breines argued that, in the context of the 1960s New Left, activists who pursued prefigurative politics “attempted to develop the seeds of liberation and the new society … grounded in counter-institutions[.]” Breines contrasts this orientation with organizers who embraced strategic politics. These politics generally involved different goals and practices, ones oriented toward building power “so that structural changes in the [existing] political, economic and social order might be achieved.” Although the two impulses co-existed within the New Left, they did so uneasily. As a result of their different approaches to change, “politicos” (who pursued strategic politics) and members of “the counterculture” (who focused on prefigurative activity) sometimes found themselves with little common ground.

Such conflicts continue to emerge today in disagreements between activists trying to influence mainstream politics and those trying to build autonomous spaces outside of it. Friction existed in Indian independence movement, too. Indeed, the multi-faceted movement ecosystem that Gandhi nurtured could only be sustained for a limited period. By the time the British had ceded rule over the subcontinent, the movement splintered back into disparate and rivaling factions.

Yet, while it can be difficult for people with different theories of change to work together, it is not impossible to overcome tensions. At its height, the Indian independence movement created levels of popular activity and mobilization rarely seen elsewhere, and it provided an example of how organizers with diverse orientations toward their work could complement each other in powerful ways. Through his personal commitment to each of the three approaches — and his ability to express a vision of them as a unified whole — Gandhi helped create a common identity for the nationalist movement. Within a thriving ecology of change, each branch of the movement could play an important role in advancing a transformative program.

An ecology of mutual support

Critical to a healthy movement ecology among Indian nationalists was the idea that each branch benefited from the contributions of the others. These benefits took tangible form.

First, the portions of the movement focused on alternatives received a major boost from the other branches of the movement — that is, from associating with Congress and with the satyagraha campaigns. Because of this association, counter-cultural stances became norms within the movement as whole. During the times of mass mobilization, movement participants were not merely asked to boycott British goods or legal institutions; they were also called upon to abstain from liquor, embrace the spinning wheel, and uphold principles of communal unity. Even though these activities had little to do with directly ousting the British, and more to do with projecting an alternative vision of Indian society, they were substantially integrated into the culture of the movement. Moreover, the mass satyagrahas greatly increased interest in the ashrams and the All-India Spinners Association.

Even though the Indian National Congress was more focused on winning formal independence from the British than building village-level alternative institutions, Congress members were influenced by the wider social movement ecosystem and adopted a variety of countercultural practices. As Brown writes, “The handspun cloth which Gandhi hailed as the symbol of a swaraj society became the virtual uniform of Congressmen who in an earlier generation had prided themselves on their semi-Western sartorial elegance.” So important was this symbol that the spinning wheel was featured on the official “swaraj flag” of the Congress party. Even today, the Indian national flag, by law, must be made of khadi cloth.

Second, the satyagraha campaigns of mass mobilization benefited from the other branches of the movement. Just as the constructive program and the ashrams were boosted by the other types of organizing taking place, the success of periodic mass protests owed much to longer-term activity. The announcement of a new satyagraha was like a declaration of war. As in war, the resources, energy and attention of the populace would be directed into emergency mobilization. This meant activating both the countercultural communities and the Indian National Congress’s networks in service of mass noncompliance.

Volunteers from the ashrams were among the most committed participants in nonviolent disruption. “When the call comes for direct action against the government” Shridharani explained, the ashrams were “transformed into Satyagrahis’ camps where the energy of the people is checked and guided into nonviolent channels.” The initial cadre who set out with Gandhi on the Salt March were members of his intentional community. In interviews with historian Dennis Dalton, former ashram residents recalled being well-prepared by their training in the ashram for the physical and emotional demands of the lengthy march, not to mention the later imprisonment and beatings they would endure at the hands of authorities. Members of the All-India Spinners Association were also reliable participants when a call to satyagraha was issued.

The nationwide satyagrahas were announced as official programs of Congress, and they were backed by the party’s organizational resources and legitimacy. Individual Congress members put their reputations on the line through participation in the campaigns. As Judith Brown writes, “Even such notable and law-abiding Indians as Motilal Nehru,” an esteemed party leader and father of the future prime minister, “now went to [jail] as an honor, though before 1921 they would have considered it a shameful disgrace.”

Third, and finally, the structure-based organizers of the Indian National Congress benefited from the other branches of the movement. For their part, politicians in Congress were willing to support mass protest (the satyagraha campaigns) and the creation of alternatives (the constructive program) not out of abstract commitment to these approaches, but because of the clear gains that their organization reaped. Periods of mass mobilization and civil disobedience allowed Congress to expand its popular reach and grassroots infrastructure, as waves of new people were drawn into political activity. In a 1966 study, Gopal Krishna of the New Delhi-based Centre for the Study of Developing Societies reported that the non-cooperation campaign of 1920-1922 coincided with a “spectacular growth of the Congress organization,” and that during this time, the group’s recorded membership “increased enormously.” Likewise, with regard to the province of Bihar, scholar Lata Singh writes that it was only as the mobilization began to gear up in 1920 that Congress was able to grow beyond its urban and professionalized strongholds and reach into the countryside.

While satyagraha served as an effective means of expanding the base of the Indian National Congress, the organization also received a boost from the work of countercultural volunteers on the constructive program. Villages whose residents directly benefited from constructive work in sanitation, healthcare, job training and education showed increased commitment and loyalty to the party. Speaking to this point, Shridharani wrote in 1939 of the agricultural workers who gained extra income through the All-India Spinners’ Association: “The farmers … are not slow to recognize that the improvement in their living conditions has been made possible by Mahatma Gandhi and the activities of the Congress. When literature and information regarding the nationalist activities are supplied by the association’s ‘depots’ and wandering scouts, they are eagerly received.”

The end of an ecosystem

The struggle against imperialism in India offers a remarkable example of a rich social movement ecology in action. That the struggle was simultaneously able to sustain itself through repeated waves of nationwide disruptive protest, to build a robust oppositional party institution, and to cultivate communities of people living in resistance to mainstream norms represents a remarkable combination of feats. Yet the movement was not free from internal tensions. On the contrary, maintaining collaboration required persistent effort. Although the ecosystem was sustained for an impressive period, divisions between different approaches to change gradually deepened. Indeed, they would lead to a split by the time of independence.

Many members of Congress, particularly those of a more moderate and lawyerly disposition, were distrustful of mass mobilization. Lata Singh describes how these tensions played out in the lead-up to the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1920. In Bihar, senior members of Congress “who believed strongly in constitutional methods of struggle opposed [passing a] resolution [to authorize the noncooperation campaign] and expressed strong doubts and apprehensions about the strategy of launching such a movement,” Singh writes. The resolution only passed after “these senior members had left the meeting in ‘disgust.’”

In subsequent decades, even as Congress repeatedly relied on Gandhi for his expertise in galvanizing public sentiment, only a portion of its members would identify as “Gandhians.” Brown argues that many in Congress extended “ambivalent and conditional support” for his nonviolent campaigns, and they were eager to return to constitutional politics as soon as mass mobilizations died down. “Gandhi accepted this limited commitment among his associates and apparent followers with realism if regret,” she writes.

A great number of Congress politicians did not closely identify with the constructive program and the alternative vision of society modeled by the ashrams. Perhaps most prominently, as Jawaharlal Nehru rose in the leadership of the party, he admitted that he did not follow the constructive program in any detail. He increasingly viewed Gandhi’s advocacy of village life as antiquated and romantic, instead advocating a program of state-led industrialization as the proper means of addressing poverty. He was not alone. Gandhi’s personal secretary Mahadev Desai wrote in 1944 that “khadi and spinning wheel were there on Congress’ program, yet only a few congressman have a living faith in … the potency of the wheel.”

In response, Gandhi and his ashramites were sometimes dismissive of Congress officials, painting them as petty parliamentarians overly concerned with their own prestige and inattentive to the actual living conditions of the poor. “Political freedom has no meaning for the millions,” he contended, without the economic improvements and cultural reforms that he envisioned achieving through the constructive program.

By the time independence was won and the Congress party assumed control of government on August 15, 1947, a vast divide had formed between these factions. Then in his 70s, Gandhi felt intensely disillusioned that only a limited version of swaraj was advancing. Having long emphasized the importance of communal unity and inter-religious harmony, he was shattered at the prospect of an impending partition of the country into Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India. Biographer Joseph Lelyveld writes of Gandhi: “[H]ere he was, at the end of his days, expressing chronic disappointment and, sometimes, a sense of defeat. He’d had more to do with India’s independence than any other individual — in declaring the goal and making it seem attainable, in convincing the nation that it was a nation — but he was not among those who celebrated.”

By the time of Gandhi’s assassination, less than six months after independence, the gulf between the politicos taking over from the British and the alternative communities organizing in the villages had grown so wide that some preeminent leaders in each branch of the movement had virtually no interaction with one another. Lelyveld writes that immediately after Gandhi’s death, “his political and spiritual heirs gathered at Sevagram, his last ashram, in a meeting that was supposed to consider how they would go forward without him … Vinoba Bhave, widely considered Gandhi’s spiritual heir, noted that he was meeting Jawaharlal Nehru, his political heir, for the first time.”

In later years, Bhave would go on to lead efforts such as the land-gift movement, aimed at getting landowners to donate a portion of their holdings to the poor. Bhave continued to establish new ashrams and to work toward village-level revitalization until his death in 1982. Meanwhile, Nehru presided over the transformation of India into a modern state with distinctly un-Gandhian features, including a well-armed military and a program of government-supported steel mills, coal mines and eventually nuclear power plants. India would see some campaigns of nonviolent direct action in subsequent decades — including the Chipko movement for forest conservation, which started in the 1970s. Yet these newer efforts would be much smaller than the major satyagrahas of Gandhi’s time.

Steps toward liberation

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this history is not that the social movement ecosystem ultimately fragmented, but that it held together for as long as it did. Over a period of several decades, nationalist forces were able to create multiple cycles of widespread uprising and to absorb the energy of these revolts into lasting oppositional structures. They managed to profoundly alter public opinion during moments of peak mobilization, as well as to sustain a culture of resistance during periods of relative calm. Each of these accomplishments is rare and laudable.

The Indian independence movement was part of a complex array of developments that led to the British departure from India, and Gandhi’s role within this history is the subject of ongoing debate. Many scholars today emphasize geopolitical factors — especially Britain’s weakened position after battling Germany and Japan — as critical in compelling the end of imperial rule. And yet, as scholar Ananya Vajpeyi argues, the social movement ecology that Gandhi cultivated had a profound effect in shaping the course of India’s history.

“No doubt the Second World War hastened the dissolution of the British Empire,” Vajpeyi writes, “but neither Allies nor Axis powers came to rescue India: in the end, India liberated itself.”

In serving as a figure who was able to bridge different organizing traditions, Gandhi provided a model of a complex social movement ecosystem. This model not only holds rich lessons for students of social movements today, it illuminates a critical idea: that transformation is most likely to come about not through any one single approach to creating social change — but through the integration of many.

Research assistance for this article provided by Will Lawrence, with special thanks to Guido Girgenti.