Organizers in labor, immigrant rights, and climate movements seeking to spark far-reaching work stoppages in the United States can invoke a powerful fact: It has happened before.

By Mark Engler

(Published on September 1, 2019 in The Nation)

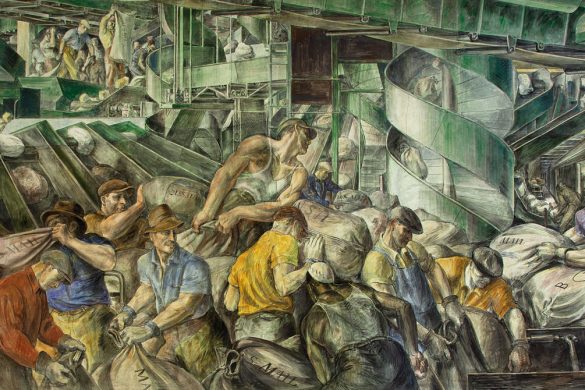

On the morning of February 6, 1919, the streets of Seattle were unusually quiet. The working people of what was then an emergent metropolis of 300,000—shipbuilders and dock workers, barbers and millwrights, teamsters and plasterers, telephone operators and garment workers, streetcar conductors and shingle weavers—overwhelmingly stayed home.

Local unions representing more than 65,000 people had voted to withdraw their labor from the economy. For five days, they joined a mass walkout to support shipyard workers who demanded higher wages amid skyrocketing inflation. Beyond union members themselves, tens of thousands of other employees were idled, as countless stores, offices, and factories shuttered their doors amid the labor unrest. The economic hub of the Pacific Northwest was paralyzed by a general strike.

The centenary of this remarkable event comes at a propitious time. Today, activists of many varieties are claiming the strike as a tool to fight seemingly intractable problems. Those talking about this form of mass protest are not limited to the labor movement, which has been inspired by recent waves of teachers’ strikes. They also include immigrant rights advocates who are calling for broad-based disruption, as well as climate change activists planning a Global Climate Strike in September.

The idea of a strike that extends beyond a single workplace or group of employees to encompass a critical mass of society has long held a hallowed place in the radical imagination. Rarely, though, is it spoken of as a realistic tactic in America. Yet those experimenting with this possibility today can invoke a compelling fact: It has happened before.

In the Seattle of 1919, union members did not merely walk off the job. They took a central role in providing social services and meeting human needs. In the labor-owned Seattle Union Record, journalist Anna Louise Strong had vowed in a defiant editorial that “Labor will not only SHUT DOWN the industries, but Labor will REOPEN, under the management of the appropriate trades, such activities as are needed to preserve public health and public peace.” Unions ran community kitchens across the city, serving as many as 30,000 meals per day. They opened three dozen sites for neighborhood milk distribution. They collected garbage and delivered oil to hospitals. Those who had served in World War I monitored public safety, and levels of crime plummeted during the strike: A commanding general stationed in Seattle remarked that he had never seen a city so orderly.

To be sure, there were serious limits to the solidarity expressed. Dana Frank, a labor historian and emerita history professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, emphasizes that the unions leading the strike excluded black and Asian workers and women from their ranks. Unions made up of Japanese immigrants joined the walkout, but they were denied a vote on strike affairs. While more radical unionists who belonged to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) opposed racial exclusion, they remained exceptions to the rule.

Yet the Seattle general strike nonetheless made a statement that altered the landscape of labor relations. “It was an enormous display of power,” Frank told me. “It didn’t just show union power to the employers, but it showed that working people could run the city themselves.” By withdrawing from business as usual, “Labor was able to say, ‘Look what we can do,'” she added. “And we carry that inside of us to this day.”

* * * * *

In the early years of the 20th century, the general strike was theorized by both socialists and anarchists as a tactic with revolutionary implications. By the time the strike broke out in Seattle, it had a litany of international precedents—and the fact that it took place in the shadow of the Russian Revolution was not lost on either its proponents or detractors. The unrest in Seattle is also not entirely unique in U.S. history. In his classic Black Reconstruction, W.E.B. DuBois characterized black workers’ withdrawal of labor from the Southern economy during the Civil War as the country’s first general strike. Other waves of labor action—from the “Great Upheaval” of 1877, to the widespread strikes of the Great Depression, to the momentous work stoppages that spread throughout the country in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War—have taken on a mass character. In 1934, a general strike in San Francisco, launched in conjunction with a wider longshore and maritime workers’ strike that affected ports along the entire West Coast of the United States, effectively immobilized commerce in the city for four days.

Since the late 1940s, however, mass strikes in the United States have all but disappeared. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 prohibited unions from joining in sympathy strikes with other workers, and the rise of “no strike” clauses in contracts mean that labor organizations face the prospect of injunctions and stiff financial penalties for stopping work while their collective bargaining agreements are in effect.

Starting in the early 1970s, the number of working people involved in any kind of strike began a long and precipitous decline. In this context, the notion of a general strike in the United States has risked becoming little more than the ardently held fantasy of isolated radicals. Some anarchist groups occasionally call for a general strike, often on May Day, without any organizing on the scale that would make it a credible threat. A one-day general strike led by Occupy Oakland on November 2, 2011 did achieve modest success as a disruptive protest—temporarily shutting down the Port of Oakland—but fell well short of halting economic activity in the city as a whole.

“There’s no question that at certain moments in history the general strike has been a thrilling and powerful tool, but you have to be careful not to romanticize because it carries real risks,” Frank said. Mass strikes in the past have been met with fearsome government repression, leaders have been fired and blacklisted, and victory is far from guaranteed. The 1919 Seattle general strike was a mixed success: It was not a victory for the shipyard workers, who continued to suffer after the wartime shipbuilding boom dried up. Yet the action was not quashed, and the tens of thousands who joined in solidarity could return to their jobs with pride, having provided a powerful example that resonated throughout the nation. “It scared the employers and created a different sense of the possible than existed before,” Frank said. “That gave working people power in indirect ways.”

While strike activity remains far below the levels of 50 or 60 years ago, the tactic is again on the rise. In 2018, more workers went on strike than at any time in the past three decades. The surge was led by teachers in the “Red State Revolt” who walked off the job in places such as West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona—but it also included Marriott hotel workers in eight cities, a citywide hotel strike in Chicago, and thousands of health care workers in California. In 2019, more than 30,000 public-school educators in Los Angeles and an equal number of employees at Stop & Shop supermarkets in New England hit the picket line.

Many in the labor movement are thinking seriously about how to build on the momentum, and some have talked openly about the prospect for mass strikes. During the Trump administration’s shutdown of the federal government in January, Sara Nelson, international president of the Association of Flight Attendants, suggested that AFL-CIO unions should join in a general strike to force the White House to back down. “What is the labor movement waiting for?” she said in a speech. “Go back with the fierce urgency of now to talk with your locals and international unions about all workers joining together—to end this shutdown with a general strike.” At a May conference celebrating the 100th anniversary of a general strike in Winnipeg, Canada—a mobilization that took place just months after Seattle and which became a landmark in Canadian labor history—labor organizer, strategist, and Nation strikes correspondent Jane McAlevey contended that, in order to fend off the international challenge of the growing fascism on the right, the labor movement should develop a 10-year plan to implement a general strike in 2030: “There is nothing more powerful in capitalist systems than workers withdrawing their labor… That’s when we win.”

* * * * *

Getting politically diverse and headstrong national unions to agree on such an ambitious plan remains a huge undertaking. Yet other possibilities for action may come from outside of the ranks of organized labor. Given that less than 7 percent of the private sector workforce is covered by collective bargaining agreements, wide swaths of non-union workers do not face the same constraints on joining with others to launch work stoppages. One key segment of this workforce is the immigrant population.

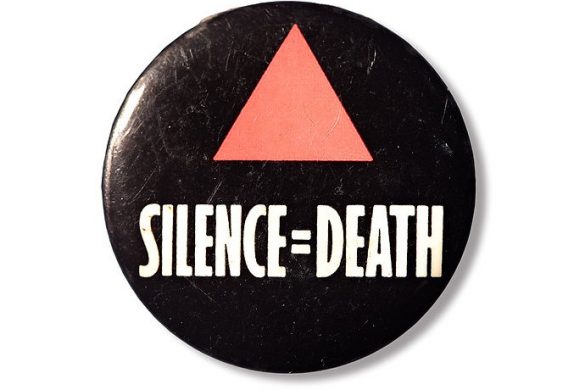

In the spring of 2006, the threat of Congress passing a piece of harsh anti-immigrant legislation known as the Sensenbrenner bill set off a series of mass protests led primarily by Latino activists. Over the course of several months, millions joined in rallies, walkouts, and mass marches in dozens of cities. “Without question, the 2006 immigrant rights actions were the biggest working-class demonstrations in U.S. history—not just in big cities like Los Angeles, but also in Indianapolis and San Jose and many other smaller places,” Frank said. “It is important to understand those as workers’ rights demonstrations.” Organizers billed one of the largest days of action—May 1, 2006—as “A Day Without Immigrants,” encouraging participants to leave their jobs in order to join protests and highlight the critical role of immigrant communities in the economy. Among the economic effects, hundreds of local businesses closed, meat processors Cargill and Tyson Foods shut down more than a dozen plants between them, and traffic at Long Beach and the Port of Los Angeles slowed to a trickle. Immigrant rights groups repeated the tactic in February 2017 to protest the Trump administration’s attacks on their communities.

Movimiento Cosecha, a social movement group fighting for permanent protections for immigrant communities, sees these actions as a prelude to something larger. “When Trump won the election, the attitude of a lot of the immigrant community was to wait out the storm,” Carlos Saavedra, director of the Ayni Institute and co-founder of Cosecha, told me. “But as deportations escalate, and enforcement escalates, and we continue to lose ground, immigrants are starting to have a shift in how they think about their safety. People are realizing they need to do something, and it’s becoming like the Sensenbrenner time in 2006.” Cosecha is organizing state-level campaigns to resist ICE and secure driver’s licenses for undocumented people, but it hopes to escalate to a general strike. (For Spanish-speakers, its website www.lahuelga.com is an explicit nod to the tactic.)

“We have hundreds of worker leaders who are organizing to figure it out, and they are talking about striking all the time in our communities,” Saavedra said. “A strike makes sense to people as a place where they have leverage—especially when they can’t vote. That’s why people relate with the idea. The way we get away from romanticization is to organize a constituency around it and develop a concrete strategy, so that it’s not just a desperation decision to take that road.”

Environmental activists, too, are looking to harness the power of the mass strike. Rather than coming from a labor-based framework, they have called for a “global climate strike” on September 20 and 27 that they envision as an extension of international student walkouts. Starting in August 2018, Greta Thunberg, then a ninth-grader, began skipping class every Friday to protest outside the Swedish Parliament. Others joined her, and in March of this year a coordinated #FridaysforFuture push from the student strikers turned out an estimated 1.4 million young people in 123 countries.

“This is the first time adults have been invited in to join the student climate strikes in a big way, and it’s happening all over the world,” said Cam Fenton, a Canada team lead at 350.org who is mobilizing participants for the climate strike. “Some people will walk out of universities, some people may be walking out of work, some might just be joining in the mass protests. But it will be about making those student strikes intergenerational.”

In many countries, relationships between climate-focused campaigners and labor unions have been vexed. American activists, for instance, have faced notable difficulties in getting unions to sign on to the Green New Deal, despite making a green jobs guarantee one of its central tenets. Nevertheless, some major labor organizations in Europe have expressed their support for the climate strike. Although legal restrictions may prevent them from officially signing on, they have encouraged their members to take part in the strike on their own accord. The German service sector union Verdi, for one, called on its two million members to participate. “Those who can should clock out and join in,” Verdi’s Frank Bsirske told the newspaper Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung. “I will be there.”

“The student strikers have been exceptionally effective at activating new people outside the usual suspects—both at peer-to-peer activation and at bringing in their families and expanding active public support,” Fenton added. “We’re seeing a generational front line, where young people have the moral authority to call in others to act.”

The September protests are unlikely to produce citywide shutdowns like that witnessed in Seattle a century ago. But like immigrant rights organizers, climate activists see mass actions as events that can trigger participation on previously unseen levels. And both hope to use them to build movements that can eventually create disruptions that merit mention alongside the storied strikes of the past.